How vaccine hesitancy is leading to a measles resurgence: A Q&A with Professor Tom Solomon

July 31, 2025

July 31, 2025

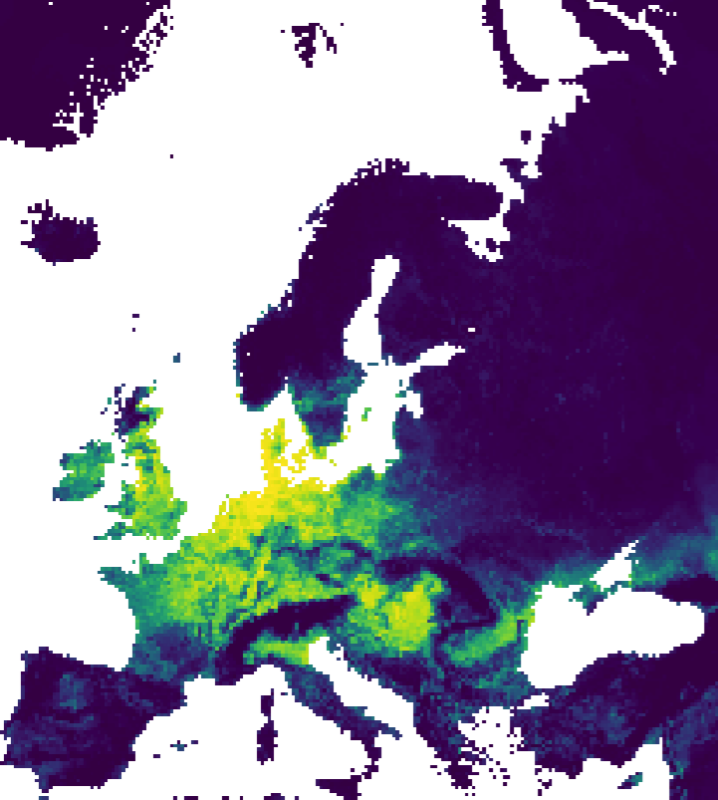

A study funded through a partnership between The Pandemic Institute and CSL Seqirus has been published in Scientific Reports. The research maps bird flu risk across Europe and, unlike earlier studies that focused mainly on landscape and climate, it also uses information about wild bird populations and how they interact with their environment. Bird flu,…

2025 has been a year of real momentum for The Pandemic Institute (TPI), as we continued to strengthen preparedness for emerging infectious diseases through rapid research funding, global collaboration, community engagement and working closely with policymakers. Accelerating research into emerging threats Responding quickly to a changing global health landscape, TPI awarded more than £700,000 in…